Derrick de Kerckhove 2020

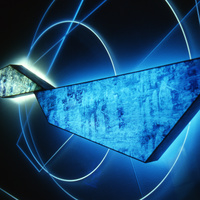

[...]Fukushi explores this new dimension of existence with the MA sensibility, seeking the intervals between natural (physical),

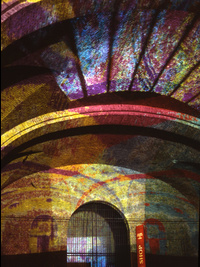

psychological (mental) and artificial (digital). Looking at page 12, the dynamism of MA is expressed by the fiery glow of the interplay between the backlit paper sheets and their shadows. And still, the ambiguity of the human (but is it still really there?) presence behind the sheets of paper querying the viewer.

Again, regarding important sensorial and perceptual differences between Japanese and others, art critic Atsushi Tanigawa observes that Ito’s work brings to mind the essay by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) In Praise of Shadows in which he discusses his preference for washi. «Western paper - he said - turns away the light» while washi, «softly takes in light to envelop it gently, like the soft surface of a first snowfall.» This key observation was also made by Marshall McLuhan, but for an entirely different reason, namely, to understand the effect and impact of television. McLuhan, like Fukushi, cultivated complementary opposites, in this particular case the difference between ’light on’, that he associated with cinema and projections on screens, and ’light through’ that, for him, brought together medieval stained glass and television. Thus ’light on paper’ focusses on the content, text or drawing. Instead the ’light through’ effect of washi focuses on the user, in this case, the reader or the art patron. Pushing the observation further, McLuhan suggested that the effect of the cathode ray tube induced a kind of ’inner trip’ in the tv watcher, thus finding a resonance with the then contemporary counterculture, psychedelic experimentation and introspective sensibility.

psychological (mental) and artificial (digital). Looking at page 12, the dynamism of MA is expressed by the fiery glow of the interplay between the backlit paper sheets and their shadows. And still, the ambiguity of the human (but is it still really there?) presence behind the sheets of paper querying the viewer.

Again, regarding important sensorial and perceptual differences between Japanese and others, art critic Atsushi Tanigawa observes that Ito’s work brings to mind the essay by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) In Praise of Shadows in which he discusses his preference for washi. «Western paper - he said - turns away the light» while washi, «softly takes in light to envelop it gently, like the soft surface of a first snowfall.» This key observation was also made by Marshall McLuhan, but for an entirely different reason, namely, to understand the effect and impact of television. McLuhan, like Fukushi, cultivated complementary opposites, in this particular case the difference between ’light on’, that he associated with cinema and projections on screens, and ’light through’ that, for him, brought together medieval stained glass and television. Thus ’light on paper’ focusses on the content, text or drawing. Instead the ’light through’ effect of washi focuses on the user, in this case, the reader or the art patron. Pushing the observation further, McLuhan suggested that the effect of the cathode ray tube induced a kind of ’inner trip’ in the tv watcher, thus finding a resonance with the then contemporary counterculture, psychedelic experimentation and introspective sensibility.

[...]

Roberto Mastroianni, 2017

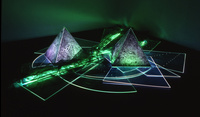

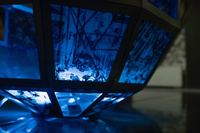

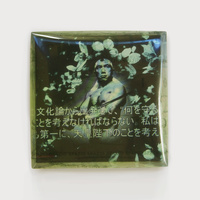

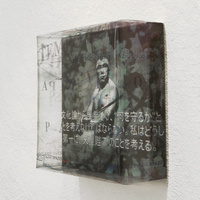

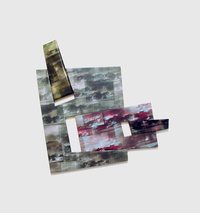

[...] Ito devoted the majority of her creative forces to investigating the nexus between space and time in works of installation and photography, yet without ever defini- tively abandoning her interest in the human scale and its exemplary nature, which was to materialise in its entirety in the cycles of works dedicated to individuals of fundamental importance to her for biographical, socio-historical or artistic reasons. These ‘exemplary figures’, with whom Fukushi has pieced together a dialogue over the intervening decades, are always representative of a socio-histo- rical specificity: they are always great creators and innovators capable of encompassing and surpas- sing the tradition they convey, becoming essential metaphors of a certain era, of a certain social and material condition and of certain discourses about the world and its transformations. They are all emblems of certain cultural specificities and have played an important role in the artist’s artistic and biographical development, while at the same time establishing the yardstick of the cultural and social horizon of this globalised age of ours, on the basis of their socio-historical import (e.g.. Machiavelli) or of their artistic or intellectual stature (e.g. Gillo Dorfles, Lucio Fontana, Bruno Munari...). In this artistic operation, which has produced and continues to produce installations of materials and com- posite languages, there is an awareness that it is not the world alone that takes shape and emerges from the aperture of space-time, but above all individual persons who are capable of giving shape to themselves and to their world, embodying elements of innovation, rupture and conservation of cul- tural, social, artistic and intellectual memory and tradition. The people with whom Ito has developed this dialogue over the years are myriad, including the great samurai of the Edo period Miyamoto Musashi, Korin Ogata, a painter of the Rimpa School, the Ukiyoe painter Katsushika Hokusai, the novelist Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Yukio Mishima, Paolo Uccello, Piero della Francesca, Leonardo da Vinci, Niccolò Machiavelli, Lucio Fontana, Bruno Munari, Oriana Fallaci, Gillo Dorfles... All individuals who come across as somehow ‘exemplary’ and ‘emblematic’, and as in one way or another exceptional in their field of history, biography and production, furnishing benchmarks for a tradition that either started with them or achieved its greatest expression or completion in them. The iconic nature of the works is achieved by superimposing realistic photographs of landscapes and of the individuals themselves onto reproductions of their writings and their works, generating a virtual landscape that produces an expanded reality, making use of digital imagery downloaded from the web or from tele- vision, among other media. By saturating and superimposing the images and projecting them into the exhibition space, using a source of light located inside the installations with a polyhedral form, the artist achieves the immersive sensation of a contemporary world populated by images and figu- res that surround our existence and form the fabric that holds the globalised world together. These works with their iconographic value are counterbalanced by the artist’s sculptural installations, which develop on edges, spheres and geometric shapes in their quest to achieve an abstract essence of the individuals as they are perceived and represented in Ito’s artistic and emotive imagery. [...]

Roberto Mastroianni, 2015

[...] Mishima is the contradictory synthesis of art and life, of West and East, of tradition and modernity: these are all elements and tensions that Fukushi has found out for herself as an artist and expatriate. The need to find a synthesis between tradition and inno- vation, between initial cultural identity and that of her place of residence, as an artist with two home- lands, has indeed placed Ito in a privileged position from which she has been able to view her original cultural context and to question it in research aimed at creating artworks that are able to stand as poetic and aesthetic bridges between two cultures. Seen from afar, today’s Japan might seem a funny place which removes a piece of its own history: it ostracis- es Mishima and all that has to do with him; it sub- stitutes the “chrysanthemum” and “sword”10 with Manga Animations and “Hello Kitty”. Seen from afar, and through Ito’s eyes, today’s Japan has not come to terms with the issues and questions posed by Mishima, by his literature and his ritual suicide. Seen from afar, from Italy, this “removal” may be tackled and thematised using the tools of the visual artist. Such prerequisites therefore demand that Ito account for herself, for her “Japaneseness” and the role of Japan in a globalised world that is more and more engaged in generalised military conflicts and geopolitical tensions; thus, the need arises to com- plete and lend organic form to her research which developed as an undercurrent parallel to the rest of her thirty-year artistic progress. [...]

Roberto Mastroianni, 2013

[...] There are artists who set their “seeing” and their “doing” in marginal areas of perception, who attempt to question reality and draw reasons from the dynamics through which these take shape, challenging the laws of seeing and the potentiality of material, seeking the logic of reali- ty: seeking the logic of emersion of that which humans commonly call “the world”. When artists embark on an operation of this type we find ourselves before an ambitious poetic exercise which, to a certain extent, tries to “dilate our perceived universe” with the awareness that our “world” is such, in so much as it is endowed with sense and meaning, and that at the same time, at the edges of this fabric of signification an “excess of sense” lies hidden which has not been encompassed within the discursive register of which reality is composed. When artists accept this challenge, we find ourselves before an artistic and philosophical endeavour which naturally advances towards investigating the criteria of possibility and the rules governing man’s presence in the cosmos, aimed at calling material into question and its relationship with the sub- ject. This is the moment when artists encounter ever-changing horizons, metamorphoses and transformations; it is the moment when matter is called into question becoming an artwork, aware that it will yield itself in “space” and “time” and that through it, spatiality and temporality will themselves be questioned. At this point, the artist stands up as a creative individual, who through “doing” produces something that is beyond the self (an artwork), which is destined to exist in the world, occupying a specific “space” and “time” and in doing so the artist accepts a challenge launched by nature and material, attempting to decipher secret mechanisms. At this point, the laws of seeing encounter the laws of representation, even during the crisis of mimetic figuration and beyond, and attempt to explain that which is visible and that which is not. [...]

Fumihiko Tanifuji, 2010

Some key words come to mind when present- ing these figures. It is a collection of people who create poetic, geometric and spatial works, bringers of light. It is a group of people who create artworks which, though showing traditional beauty, are also bearers of innova- tion. It is a group of people who create aes- thetic works of rare calibre. It is a group of peo- ple who create works demolishing stereotypes and seeking avant-garde expression.Each icon is created using a complex superimposition of images, images of the figures in question, urban landscapes, images of works and man- uscripts that are linked to them. Such match- ings link Yukio Mishima to the Golden Pavilion and Machiavelli to Florence. As a matter of principle they all use images taken from the internet, television or digital photographs and Ito presents them under the concept of “virtu- al landscapes”. Alongside the real landscape, we who live in the contemporary world are also surrounded by a virtual landscape. In McLuhanian terms, it is a “dilated” reality in which we live transcending time and space. The artist herself has been profoundly inspired by the figures she has chosen, but this inspira- tion is not only the fruit of a direct encounter with them or their works, indeed a significant role is also played by informational elements obtained through media such as television, publishing and the internet. The computer drawings that come into being therefore are not in a strict ratio of one person, one image, indeed they number over a thousand. In the experimental phase it is said that Ito created several thousand images. These computer drawings are printed in photograph quality on transparent PVC and applied to stainless steel frames that form 62-faced polyhedrons. More- over, the artist has left some of the faces with- out anything attached. Here the issue of per- meability comes into play. For some time Ito has painted on Japanese paper, which is per- meable, but in this case it is not just the image itself that permeates, through the open win- dow it is possible to peek inside the polyhe- dron which reminds us of a sphere and it is equally possible that we can also see the back of the images. This is considered a decisive measure to annul the level of materiality in a virtual image.

Flaminio Gualdoni, 2010

[...] it has to do with Fukushi Ito’s personal story whereby living, being in two homelands, is neither a sacrifice nor a loss, nor does it imply ambiguity, subtraction or compromise, it is a further synthesis that loses none of its constituent elements, instead it nurtures and empowers both, becoming a new, fuller iden- tity. It was Bauman who pointed out how this “liquid modernity” – this is how he defines the post-modern condition – in other words the fluidity and continuous modification of the ele- ments on the ground, have shed light on the manner in which the formation of identity is a twofold process, comprising construction and constriction. Some factors pertain to the per- ception and definition of the self that an indi- vidual establishes, others are received and, in some cases, imposed. But Ito is no such case. Ito is a citizen of art, and art, by its very nature, is sheltered from the logic of constructive or constrictive programming, precisely because it understands the value of identity as a critical, problematic factor, and, most important of all, it is not static. Identity is what you are, but fur- ther identity is what you can and want to become, acting as an artist.[...]

Flaminio Gualdoni, 2009

Fukushi Ito’s works have the transitory charac- ter of something that fills the rift between East and West. There is always something that escapes, yet the artefact statically presented to the observer as an artwork redeems itself in a world of hope, changes and fleeting new evocations. Whether in the romantic south or the Germanic north, Europe is used to clear statements, be they rational or emotional. But there must be a balance between these two poles, gut and brain, an intrinsic certainty that nonetheless remains open to everything that is laid out before us, or within us, capable of visualising our future. In this monumental work Fukushi Ito shows how these juxtapositions, which the Europe- ans often consider as irreconcilable contradic- tions, can flow into each other in a comple- mentary thought process that can become reality through art: this is the balance between contrasting energies, between negative and positive, between masculine and feminine, between rational and irrational which leads one to the other, meeting and amalgamating thanks to a universal pantheistic energy that reconciles and pacifies the Yin and Yang in a Plotinian “One”.

Rita Matano, 2008

Central to this artist’s research is the uneasy balance between nature, its heritage, and eve- rything that humankind produces as wealth. Thus, the planet Earth is suspended in a sort of symbolic net soaked in the natural element of water. The Axes X and Y depict the rela- tionship between economy and art, in other words between wealth and human resources. It is clear that by deciding to use the Cartesian coordinates the artist wishes to make a direct reference to the more usual language of the economy and the language of her own depic- tion. [...]

Marco Meneguzzo, 2007

[...] In her most recent works, Ito seems to have stressed a vaguely “political” side of this recomposition, through two closely linked pro- cesses: she has chosen to employ images tak- en from television news broadcasts, and she has taken strong images, immediately recog- nisable and related to facts, these she has mixed with neutral images of landscapes. Within this twofold, single action – television is, for better or worse, linked to the concept of mass communication – Ito has underlined the concept of fragment while multiplying, among other things, the same figure and the same fragment of a story: be it the brazen and some- what rhetorical, though effective countenance of Oriana Fallaci, or a typical landscape on a road in the middle east where some attack is sure to take place, this multiplication of imag- es leads to visual saturation and interpretative paralysis. Millions of images that are all the same fill our imaginations on a daily basis and prevent us form reconstructing a coherent sto- ry, yet in our hearts we know that that story exists, it must exist: at least the difficulty of this fragment of a fragment makes us aware that we once believed the story made sense.

Atsushi Tanigawa, 2001

[...] Ito’s work brings to mind the essay by Junichiro Tanizaki ( 1886-1965 ) In Praise of Shadows in which he discusses his preference for washi. “Western paper,” he said, “turns away the light” while washi, “softly takes in light to envelop it gently, like the soft surface of a first snowfall.” I have no idea whether Ito had Tanizaki’s arguments in mind or not when she selected washi as a backing material but she is clearly aware that washi simultaneously func- tions to both absorb light and to allow it to per- meate the surface. In fact, she makes strategic use of this quality. We could classify Ito’s work as part of the Light Art movement which began in 1960 if we overlooked the fact that Light Art is generally composed of naked neon lights and the fact that not all of her work even involves neon. No, in my opinion, this work belongs in a different category, if not dimen- tion. It would be closer to the truth to speak of Ito as haviong replaced paint with neon to express sensibilities which I suspect have been influenced by living in Italy where stone is the long established building material. [...]

Toshiaki Minemura, 1999

[...] In italy, Ito must have comprehended the notion of spatial dynamism inherited from Baroque and explored by Futurism and Spa- tialism. Needless to say, the artist’s concern lay not in an actual Kineticism but a latent dymamism compatible with Rinpa’s legacy. Which is to say, in a space that undergose the generative process, from constantly interpene- trates space and matter can manifest itself as light. This idea, aside from the dimension of acutual motion, could have provided a solu- tion to what Ito was seeking in a horzon opened up by Rinpa. In other words, the inter- vention between fragmenting forms and space, and the metamorphosis of a pictorial matière free from formal constriction into a phenomenon of light, were simultaneously a legitimate evolution from Rinpa painting and an equally legitimate. though personal and specific, extension of Baroque/Futurist/Spa- tialist Art. [...]

Shuji Takahashi, 1999

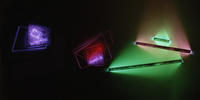

[...] The source of illumination exists on the other side of a filter of Japanese paper, which may be colored or in recent works covered with computer-generated drawings, while the tips of the geometrically cut acrylic plates reflect sharply tzs which cannot be included in the traditional Light Art that presents light or itself or its changes.

The effect of Japanese paper, which trans- forms the inorganic element of neon light into something imbued with warmth, is given an even more multiplex quality through the addi- tion of computer-generated drawings. Ito, however, who calls computers “pencils of the twentieth century,” has no intention of relying solely on technology. Her work is distinguished from traditional Light Art in that light is not the sole important element; instead, neon, Japa- nese paper, and computer-generated draw- ings are all component elements of the same rank that give form to the artist’s views of nature and humanity. [...]

Dieter Ronte, 1997

[...] Europe is used to making clear state- ments, whether rational or emotional, souther- ly romantic or northerly Germanic. But there has to be a balance between these poles of stomach and head, an inner certainty that yet manages to remain open to everything that lies before us, that is in us, that visualises our future. Fukushi Ito demonstrates that these juxtapositions, that Europeans often have to assume as uncomptomising contradictions, can flow together into a completo assume as uncompromising contradictions, can flow togher into a complemetary thought process that can became reality through art.

Martina Corgnati, 1994

[...] Softened, inviting shapes that balance out other more jagged, harder ones in an alert jux- taposition, just as the order of the day balanc- es that of the niglt, pretence balances the truth and nature, which in the personal symbology developed by Fukushi Ito is represented by paper, balances culture, or rather technology (neon). And what could be more oriental than the firm belief in two opposed and dialectic polarities that supervise the world’s dynamic existence in their reciprocal interpenetration and alternating manifestations? And yet this is no matter of nostargia, of Sehnsucht, not yet of destiny, vocation or essence, as Fukushi Ito has broken free of the (cultural) confines with- in which her origins would have relegated her; with the tenacity and enthusiasm that only the real traveller has, she has shaken off the shackles and traditions of one place in favour of another place. Not so much as a way of assuming a different appearance, exotic because it would be unlike her own, but to refloat her creative freedom off the shoals of a highly ritualised tradition, suffocated by weighty unconsumed influences, formal dik- tats that are ill at ease with an authentic, mod- ern quest for one’s personality, whatever tha case.[...]

Jürgen Schilling, 1994

[...] At first sight, she opens up a subtle dichot- omy with the dimention of the environment, the action “between time and space”, as Ito herself call it, that moves on many planes at the same time and has the ability to irritate the observer. There are the white, green and red light sources with their differentiated qualities of light, that not only shine partly through the overlapping layers of paper streched over the canvas, but are also capable of shaping space, so that, because of the property of the precise- ly balanced and arranged sheets of plexiglass, the light reaches the sharp edges and illumi- nates; so that, apart from the surprising effect, clear contours are formed far away from the centre. The optical effects are confusing. But shadow also has a part to play, when Fukushi wants to achieve convincing plastic effects and give the impression of the illusion of space. [...]

Vittorio Fagone, 1991

[...] The procedure adopted by the artist dis- closes, in the first place, the physical continu- ity of the sheet of paper which, far from being inert, despite its geometrical confines, almost breathes under the pigment. The pigment, in fact, appears both interpenetrated and exten- sive, constituting the encounter of two differ- ently orientated yet equally meaningful physi- cal agents.

The colour is a natural, retted element treated by the artist; it tends to preserve, along with its effusive presence, a kind of primary from and substance. And so too is its resolutionary, intense and – perceptively – captivating arrangement. It is at this point that, in Ito’s more recent work, both densely-coloured and artificial light (neons) come into play. This dis- tances and establishes oblique dialectics between these essential “issues” – colour and paper – thereby revealing an ambiguous and complex presence which tends to confine itself to the undeniable and complex play on presence. Shown in the dark, each of these presences reveals itself in the immaterial spe- cific expression of an incessant flowing forth of light/colour and in its being a fragile and paradoxically extensive yet distant essence. [...]

Marisa Vescovo, 1990

[...] when Fukushi ito presents us with her displays of light, we know that the artist wants to arouse in us the feeling of things which rise to the surface from the darkness of invisibility, as light also reanimates the memory of what we have seen in the past and what it has not been possible to see. She uses neon light as the indicator of an energy coming from the culture of technology and joins it, or rather subjects it to the natural material of the paper. For an Oriental like Ito, nature is not in oppo- sition to man, but constitutes her essence. The use of light, of rice paper, of transparent plexiglass, of four-element geometry to con- struct her works, makes us think of the world as infinite return play of signs, an interplay of reciprocal influences, which is presented as an organism operating according to its own order, where the possibilities for action are infi- nite. The image of the whole which is expressed is always the symbol of visibility and, as such, must assert itself for its power of resonance. The first opportunity to obtain effective resonance comes on the visual, per- ceptive level, that is, in the relationship with light.[...]

Pierre Restany, 1987

The objecthave 人, the inverted 入 on the contrary and the theedimentional expression of the japanese sign “men” that is “Hito“. The structural balence of the symbol, in which one line leans on another, reminds us that man dosen’t exsist only for himself.

Franco Solmi, 1985

[...] The unceasing fluctuation, expansion and continuous withdrawal of forms, the nuclei so clearly held by the artist within an image that ignores “good” forms, and contains only con- tinuously reproposed rhythms escapes our sense of measure, but not our sentiment. Ito paints surfaces, a superbly woven, vibrant, penetrating surface, and if it dose not lacerate from a secret need to confuse solids and hol- lows, space and time, it nevertheless is charged with unresolved tensions and a gen- tle, but unyielding drama. Faced with these “textures”, in short, one realizes just how right Valery was when he stated the poetic paradox that “the skin is deepest”. [...]

Giorgio Segato, 1985

[...] The technical processes which enhance antique japanese papers, the preference for mineral colors, the setting over and transpar- encies of colored veils, the dilutions and con- stantly exercised gestures (the paper is wrin- kled before it is glued on the support in order to obtain surprisingly mobile volmetic effects), all reinforce the cultural bond with the native land, and with a significant capacity for elabo- ration and formal synthesis, indicate an explic- it desire for internal equilibrium with which to compare and evaluate impulses and stimuli from surrounding reality and one’s cultural herediy. In Fukushi Ito, the sign seems to develop with vertical prospective, and seek tendencies of intimate harmony and musicali- ty. These canvases give the impression of a deep breath which dilatates space, enlarging it with perceptions of a rich contemplative and romantic vitality, nocturnal, lunar sensitivity. In the ambiguos space (internal/external, psy- chic/physic). Ito finds and shows itineraries of light, nuclei of emotion/vision, sinuous and elastic signal routes which take on consisten- cy and mobility thanks to a sage material superimposition and intervening gestures. [...]

CONTACT

CONTACT